- Home

- Kevin Elyot

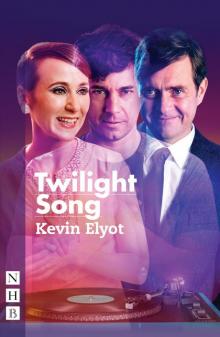

Twilight Song

Twilight Song Read online

Kevin Elyot

TWILIGHT SONG

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Characters

Twilight Song

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Twilight Song was produced by Cahoots Theatre Company and David Sloan in association with Park Theatre. It was first performed at Park Theatre, London, on 12 July 2017. The cast was as follows:

HARRY

Philip Bretherton

SKINNER/GARDENER

Adam Garcia

ISABELLA

Bryony Hannah

BARRY/BASIL

Paul Higgins

CHARLES

Hugh Ross

Director

Anthony Banks

Designer

James Cotterill

Lighting Designer

Tim Lutkin

Composers & Sound Designers

Ben and Max Ringham

Dialect Coach

Elspeth Morrison

Dramaturg

Sebastian Born

Production Manager

Nick May

Company Stage Manager

Cassie Gallagher

Assistant Stage Manager

Leanne James

Characters

SKINNER

BARRY

BASIL

ISABELLA

CHARLES

HARRY

GARDENER

Setting

The play takes place in the same sitting room of a Victorian villa in North London during the early summers of 1961, 1967 and the present day.

A door leads into the rest of the house. A double-doored French window leads into the garden. The furniture includes a sofa and a 1920s mahogany gramophone cabinet. There’s a fireplace with a mirror above it.

Doubling

SKINNER and GARDENER are played by one actor.

BARRY and BASIL are played by one actor.

Scene One

A grey drizzly afternoon in May, unseasonably dark. A barely discernible veil of mist shrouds the untidy room which seems to have seeped in from outside. A Bose radio/CD player stands on a table next to the 1920s mahogany gramophone cabinet. SKINNER (late forties), smartly suited, at the French window, looking out at the rain; BARRY (mid-fifties), watching him.

SKINNER. Live alone, do you?

BARRY. No. With my mother.

SKINNER. Where’s she then?

BARRY. Dunstable.

SKINNER. Just the day for Dunstable.

He looks around.

Been here long, have you?

BARRY. Getting on for fifty years or more.

SKINNER. Fifty years, eh?

BARRY. All my life, actually.

SKINNER. Suffered any slippage?

BARRY. Well, I’ve had a few problems but –

SKINNER. Subsidence?

BARRY. Oh, I see. Yes, this whole area – you can’t move for cracks.

SKINNER. Very nice though. You couldn’t be better located.

BARRY. You think so?

SKINNER. Almost recession-proof.

BARRY. Well –

SKINNER. Believe me.

BARRY. Right.

A gurgling of water pipes from upstairs.

SKINNER. It used to be part of the Great Forest of Middlesex, you know.

BARRY. Had it?

SKINNER. Oh yes, I’ve done my homework. A case of having to now we’re getting a bit more international. Americans love a little snippet like that: the Great Forest of Middlesex.

BARRY. I never knew there was one.

SKINNER. Of course it hasn’t existed for years. Chopped down by Henry the Third.

BARRY. Henry the Third?

SKINNER. In the thirteenth century.

BARRY. Why would he go and do a thing like that?

SKINNER. Robbers, so they say.

BARRY. Really?

SKINNER. The place was swarming with them.

BARRY. Good heavens.

SKINNER. Ah well, plus ça change.

BARRY. Yes, quite.

SKINNER. That’s the trouble with royalty: think they own the bloody place.

A sudden grating, cranking sound.

BARRY. That’ll be the fridge. We’ve been meaning to get a new one but…

SKINNER. Your compressor needs replacing.

The sound continues.

BARRY. It’ll stop soon.

They wait. It stops.

That’s better.

SKINNER. Not that I’ve got anything against the present incumbent, God bless her. She’s a diamond: solid, reliable, just like my Audi. I just wish she’d chill out a bit, know what I mean? Always looks like she’s got a knob of ginger stuck up her arse.

BARRY. Can I get you anything?

SKINNER. Not while I’m on the job.

BARRY. No, of course.

SKINNER. What’s she doing in Dunstable then?

BARRY. My mother?

SKINNER. Yes.

BARRY. She has an appointment.

SKINNER. An appointment in Dunstable, eh?

BARRY. She has one every Thursday.

SKINNER. Hospital, is it?

BARRY. Not exactly. In fact, she’s doing pretty well, considering. I think I’ll conk out before her what with this and that, and my heart’s not too clever – that’s what did for my dad. Have you got a mother, Mr Skinner?

SKINNER. Skinner, please.

BARRY.…Right.

SKINNER. No, I haven’t. She died when I was a baby.

BARRY. Oh dear.

SKINNER. Didn’t know anything about it, did I? Then my dad upped sticks and we went down under. He’d got a bit of money, see – I’m not sure how – and went through it like a tit in a trance. Ended up in Wagga Wagga.

BARRY. I’ve not heard of that.

SKINNER. About as exciting as Swindon on a wet Sunday.

BARRY. I thought you had a little twang.

SKINNER. Eh?

BARRY. Your accent, just a hint of… whatever.

SKINNER. Yeah. Clings like crabs.

BARRY. Were you there for long?

SKINNER. I was back here like a shot once they let me out of youth offenders’. Dad had drunk himself to death, see, and I went a bit off the rails.

BARRY. What had you done?

SKINNER. This and that, but I’m well-reformed now. I learnt all sorts in there: plastering, life skills, and a few positions even the Christian Brothers never got round to.

BARRY. You were taught by the Christian Brothers?

SKINNER. I’d swing for those cunts, pardon my French. Let your hair down, do you, Mr Gough?

BARRY. I’m sorry?

SKINNER. On a Thursday, when your mum’s in Dunstable?

BARRY. Not exactly. I’m not the hair-letting-down type – although I used to… let it down. In fact, I let it down quite a bit… and even now, if I think about it, once in a while… I’ll let the odd lock… drop.

SKINNER. You’ve got to live for the here-and-now, haven’t you? No use putting it off.

BARRY. That’s what Mother says. ‘You’re letting it slip away, Barry. One simply has to get on, get a grip.’ She says it quite a lot, actually.

SKINNER. Sensible woman, your mother. Yeah, I can imagine you’re a bit of a goer on the quiet.

BARRY. Well, I wouldn’t quite say that…

SKINNER. Always the quiet ones.

BARRY. And I wouldn’t say I’m that quiet.

SKINNER. So what do you do, if you don’t mind my asking? Or are you one of the idle rich?

BARRY. No I’m not. I was gi

ven early retirement.

SKINNER. Happens a lot now, doesn’t it?

BARRY. Yes. I worked in a pharmacy, the same one nearly all my life. The years I gave to that place… Mother wanted me to be a doctor but I never quite cut the mustard. I thought I’d made a fair enough compromise but she of course didn’t, and all the time what I secretly wanted was to be a dancer.

SKINNER. Oh yeah?

BARRY. Then it transpired I had Policeman’s Foot.

SKINNER. Nasty.

BARRY. It is. Intermittent, but very painful.

SKINNER. I once had a mate who wanted to be a bouncer.

BARRY. Really?

SKINNER. Yes, but he had Doorman’s Knob.

BARRY. It’s hard, isn’t it? Thwarted ambition.

The water pipes gurgle again.

I sometimes think about getting a little job but it’s not that easy, and the older you get, well… That’s why I’m curious about the value in case we have to downsize.

SKINNER. So what do you do with yourself all day?

BARRY. Oh, I keep myself busy. Go out… stay in. I do see the odd exhibition or… friend, although… it’s strange now wandering around London. It’s full of memories: a restaurant, a park, a corner. That’s where I did such-and-such with so-an’-so all those years ago, and of course they’re not there any more. All dead or moved on. Like a cemetery.

SKINNER. Funny old place, isn’t it? The other day I saw a bloke on one side of town, then the next day I saw him on the other. Imagine!

BARRY. But I wouldn’t live anywhere else. I couldn’t, not now, because of Mother.

SKINNER. Not exactly a barrel of laughs then.

BARRY. I don’t think it was ever meant to be.

SKINNER. Certainly not round my gaff, I tell you.

BARRY. Do you have a family… Skinner?

SKINNER. Just the wife, and her bloody mother who’s always sniffing around. I tell you, it’s all moaning, misery and death in my house. That’s all I got, Mr Gough. As soon as I walk through the door, I feel my balls shrivelling. Leave them to it, it’s the only way.

BARRY. You don’t have children?

SKINNER. No, thank God. Christ knows how they’d have turned out. (Glancing out at the garden.) Now that’s odd: looks like you got a bit of a terrace out there.

BARRY. Yes, we have.

SKINNER. Intentional, like?

BARRY. No. We just ran out of…

SKINNER. Money?

BARRY. Interest, really. Thought it was a good idea, then… never got round to finishing it.

SKINNER. That is a pity, cos when the weather’s nice, you could have sat out there with a little drinkie. Fancy, fifty years and no terrace. The missus wouldn’t have let me get away with that.

BARRY. Does she keep you on a tight rein?

SKINNER. When she can. Now, I love my football, go to the match, have a bit of a kick-around some Sundays, but she says I’m neglecting her. I ask you! And you know what she did? Only went and burnt my boots.

BARRY. Oh dear.

SKINNER. Like a bloody brownshirt!

BARRY. Couldn’t you buy some more?

SKINNER. I did, but they’re hidden in my shed. I thought that was well beyond the pale, Mr Gough. How would you feel if someone burnt your boots?

BARRY. I don’t have any.

SKINNER. Well peeved, I reckon.

BARRY. I never have had.

SKINNER (re: ceiling). Very nice bit of moulding up there. Nice bit of egg-and-dart, not too flash. Pity about the damp patch. You know what I think, Mr Gough? I think your mum’s playing away.

BARRY. What?

SKINNER. Appointment in Dunstable? Pull the other one!

BARRY. No, I assure you, she’s not… playing away, as you put it. She sees someone every Thursday.

SKINNER. That’s what I’m saying.

BARRY. A spiritualist.

SKINNER. Oh.

BARRY. She… lost someone, you see, many years ago now, and she’s never got over it. She’ll do anything to try and make contact, even with the spirit world, in case he’s passed over.

SKINNER. Right. Me and my big mouth.

He looks out of the window. The rain’s heavier.

(Re: the rain.) It’s coming down now.

SKINNER watches it. BARRY watches him.

Mate of mine, a deal younger than me, joined the army. Football mate, you know? He tried to get me to – get me out of the house, new life, new way of seeing things – but I couldn’t face it.

BARRY. It has its downsides.

SKINNER. Ended up in Afghanistan.

BARRY. Good heavens.

SKINNER. Oh, he loved it out there. Said it made him feel alive for the first time in his life.

BARRY. Well, there you go.

SKINNER. But he didn’t make it. When his coffin was carried out the plane, I had a lump just here – (Indicating his throat.) like a brick. And it wasn’t because he was dead; it was because his wife was there with his little boy and his mum and dad, trying to hold themselves together, and I thought if I was in that coffin, who’d be there to cry for me?

BARRY. Your wife, your mother-in-law –

SKINNER. No one, and it was because of that I could have wept. What’s the penalty for a wasted life, eh?

BARRY. But he didn’t waste it; he died for something he believed in.

SKINNER. I mean me, Mr Gough. My life. Ever asked yourself that? It gets you sometimes, it really does.

He looks out of the window again. BARRY’s at a loss, then:

BARRY. You’re surprisingly sensitive… for an estate agent.

SKINNER. It’s getting dark already. I hate the night. Never know what’s going on. Sometimes I wake up and can’t breathe.

BARRY. Panic.

SKINNER. Yes, or the wife with her hand clamped over my face to stop me snoring – like Alien.

The grating, cranking of the fridge starts up.

(Re: fridge.) How do you live with that?

BARRY. You think this’d fetch a decent price then?

SKINNER. Victorian villa? This location? Worth its weight, Mr Gough, even in this state. So you’re thinking of selling?

BARRY. Well… I’d like to know what I might be getting… whenever. Money is a little tight these days.

SKINNER. You’re not kidding. The old estate agenting’s been rough this past year or two.

BARRY. Everyone’s feeling the pinch.

SKINNER. All in it together, eh? I don’t think so! Fucking lard-arsed Etonians, if you’ll pardon my French. Yes, Mr Gough, pretty rough it’s been. I’ve had to take on a little bit extra to keep my head above water.

BARRY. What else can one do?

SKINNER. Think outside the box, that’s the trick of it. Now a brickie mate of mine, he’s taken up aromatherapy.

BARRY. I wouldn’t have thought of that.

SKINNER. Exactly. You’d be surprised what people come up with. Round where I live, there’s all these women stuck at home and they appreciate the occasional treat, Mr Gough. They like a bit of the old scented oil.

BARRY. And what do you do?

SKINNER. Fuck people. Now that’s one nice fireplace you got there, Mr Gough. Yes, women, men. In my book, every hole’s a goal.

BARRY. I must say, I’m rather taken aback.

SKINNER (looking at the ornaments on the mantelpiece). I thought I might be a bit long in the tooth, but you’d be surprised how many go for the maturer man. Do you have a partner, Mr Gough?

BARRY. Yes. My mother.

SKINNER. Man’s best friend.

BARRY. You know, sometimes I think I should just get up and go, leave her to it, but I never do. I always find myself standing here like a child as if all the years that have passed were as nothing, craving her indulgence and awaiting her approval.

SKINNER. Hang on, man’s best friend’s a dog, isn’t it?

He bends over to inspect a scuttle in the grate. BARRY can’t resist a peek.

Very nice… oh yes, I like that. (Straightening up.) You’ve got some tasty artefacts, I must say.

The rain intensifies. SKINNER looks out at it.

Ne’er cast a clout, eh, Mr Gough?

BARRY. No…

SKINNER. Oh well, who knows what’s round the corner, partner-wise?

BARRY. I’m afraid my sentimental side’s somewhat muted now. The last time I felt more than the usual stirrings was in Venice. I’d gone with my mother for a long weekend, but she ate a dodgy clam and took to her bed. He was a waiter at the hotel and had that Italian twinkle that’s quite hard to fathom. I took him for a very nice lunch that lasted till dusk, but even as we spoke, and the sun set behind the Salute, I felt that familiar disappointment as we slowly sank into the sludge.

SKINNER. Now that’s somewhere I’ve always fancied – Venice. A touch of the Cornettos on a gondola.

BARRY. You should take your wife…

A look from SKINNER.

Perhaps not…

SKINNER (re: the old gramophone). Does this still work?

BARRY. Oh no, we haven’t used it for years. It’s a family heirloom, an ugly piece really. We’ve just never got round to getting rid of it. (Re: the house.) So you don’t think we’d need to do it up then?

SKINNER. You’d be wasting your money, Mr Gough.

BARRY. Not even a coat of paint?

SKINNER. Not even a lick.

BARRY. Well, that’s… most informative.

SKINNER. What I’m here for.

The rain pours.

BARRY (with great difficulty). I wonder, would you… would you ever consider…? I mean, might it be possible to… to see your way to… doing it with me… perhaps?

SKINNER looks at him.

SKINNER. Ooh, I don’t know, Mr Gough.

BARRY. No, I understand. I do, really. I mean, why on earth would you fancy me?

SKINNER. Fancying doesn’t come into it. I have catered for the older market. It’s just the practicalities, you see. I feel a bit uncomfortable during office hours.

BARRY. Maybe another time…

SKINNER thinks for a moment, then:

SKINNER. Anything in particular you go for?

BARRY. No, I have… fairly catholic tastes.

Beat.

SKINNER. I know all about them, believe me.

Twilight Song

Twilight Song